THE SOPRIS SUN,Carbondale’s community supported newspaper • May 22,2014 • 13

Sopris Sun Staff Report – Former Buddhist monk/counselor/teacher John Chophel Bruna has partnered with long-time local Laura Bartels to create the Mindful Life Program, offering practical and transformative courses, retreats and re- sources in mindfulness. Based in Carbondale at the Third Street Center, they offer pro- grams locally and throughout the U.S., Canada and Australia to help participants live a meaningful life according to their own values, and learn to respond skillfully to life’s events, said a press release.

Bruna is the director of the Way of Compassion Foundation and co-founder of the Mindful Life Program. Not unfamiliar to the Roaring Fork Valley, Bruna, who was a Tibetan Buddhist monk for more than six years, used to tour with his fellow monks from Gaden Shartse Monastery through Aspen and Glenwood Springs. Having moved to Carbondale last summer, he now has a steadily growing number of people from the area studying with him and attending weekly groups, retreats and trainings.

Bruna’s journey to Carbondale is un likely. When he was growing up amid poverty, drugs and violence in Los Angeles, one of nine children of a widowed mother, he had one goal: to not go to prison like family members and friends.

Despite stealing alcohol from liquor stores at age 10, becoming an alcoholic, a drug addict, homeless and a father at 20, Bruna managed to achieve that goal, according to a press release. But at 22, as his life spiraled out of control, he decided to get clean and sober and set a new goal: God’s will be done, not mine.

“My will always got me in trouble,” he said. “For me, it translates into: How can I be of benefit?” Fifteen years into recovery, another pivotal event came when he started to meditate and follow the Buddhist teachings of the Dalai Lama.

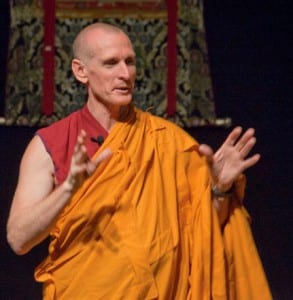

John Bruna

“I realized that much of the suffering in the world is unnecessary,” said Bruna, who in 2005 became an ordained Buddhist monk in the Tibetan tradition. “To have real peace in life, you have to have peace with yourself. Meditation allowed me to quit reacting to the world and to be able to respond skillfully with intention. I was able to go inside and look at the patterns in my life that led to unhappiness and ask myself: What will help me lead the life I want, a beneficial life?”

Today, Bruna travels the United States and Canada giving workshops and leading retreats designed to help others lead happier lives. He is currently teaching a four- week mindfulness course in Carbondale. He also leads a weekly Mindfulness Group, and a weekly meditation and dharma talk. “The quicker we identify our emotions, the more skillfully we can respond to them instead of simply reacting to them,”

Bruna said. Bruna said he believes that one of the best ways to become aware of one’s emotions and respond appropriately is through cultivating mindfulness throughout one’s daily life, which is an integral part of his teachings. Mindfulness, even practiced for a few weeks, can transform lives, according to Bruna. The key to mindfulness is training the mind, which is done through meditation. “Meditation settles the mind, bringing it back to its natural state,” he said.

At the end of 2011, Bruna said he transitioned from the life as a Tibetan Buddhist monk to a layperson because he felt he could be more effective, reaching more people as a layperson than as a monk. In 2012, he founded the non-profit Way of Compassion Foundation, with the mission of helping people live meaningful lives according to their own values and spiritual beliefs. The foundation operates on donations he receives from his workshops and public talks and from sponsors. Desiring to offer mindfulness training that was practical, accessible and universal, Bruna, along with Australian colleague Mark Molony, created a curriculum for a comprehensive mindfulness course that is adaptable to all types of specific audiences from the general public, to educators, therapists and recovery programs among others. The goal is to help participants live a meaningful life according to their own values, while cultivating emotional and “attentional” balance.

For more information about the weekly groups of both organizations see mindfullifeprogram.org and wayofcompassion.org, or call 970-633-0163.

The Wisdom of a Meaningful Life

$15.95 US

The Wisdom of a Meaningful Life

$15.95 US

The Essential Guidebook to Mindfulness in Recovery

$19.95 US

The Essential Guidebook to Mindfulness in Recovery

$19.95 US

Daily Practice Journal

$12.00 – $42.00 US

Daily Practice Journal

$12.00 – $42.00 US

Bruna, Bartels launch Mindful Life Program

THE SOPRIS SUN,Carbondale’s community supported newspaper • May 22,2014 • 13

Sopris Sun Staff Report – Former Buddhist monk/counselor/teacher John Chophel Bruna has partnered with long-time local Laura Bartels to create the Mindful Life Program, offering practical and transformative courses, retreats and re- sources in mindfulness. Based in Carbondale at the Third Street Center, they offer pro- grams locally and throughout the U.S., Canada and Australia to help participants live a meaningful life according to their own values, and learn to respond skillfully to life’s events, said a press release.

Bruna is the director of the Way of Compassion Foundation and co-founder of the Mindful Life Program. Not unfamiliar to the Roaring Fork Valley, Bruna, who was a Tibetan Buddhist monk for more than six years, used to tour with his fellow monks from Gaden Shartse Monastery through Aspen and Glenwood Springs. Having moved to Carbondale last summer, he now has a steadily growing number of people from the area studying with him and attending weekly groups, retreats and trainings.

Bruna’s journey to Carbondale is un likely. When he was growing up amid poverty, drugs and violence in Los Angeles, one of nine children of a widowed mother, he had one goal: to not go to prison like family members and friends.

Despite stealing alcohol from liquor stores at age 10, becoming an alcoholic, a drug addict, homeless and a father at 20, Bruna managed to achieve that goal, according to a press release. But at 22, as his life spiraled out of control, he decided to get clean and sober and set a new goal: God’s will be done, not mine.

“My will always got me in trouble,” he said. “For me, it translates into: How can I be of benefit?” Fifteen years into recovery, another pivotal event came when he started to meditate and follow the Buddhist teachings of the Dalai Lama.

John Bruna

“I realized that much of the suffering in the world is unnecessary,” said Bruna, who in 2005 became an ordained Buddhist monk in the Tibetan tradition. “To have real peace in life, you have to have peace with yourself. Meditation allowed me to quit reacting to the world and to be able to respond skillfully with intention. I was able to go inside and look at the patterns in my life that led to unhappiness and ask myself: What will help me lead the life I want, a beneficial life?”

Today, Bruna travels the United States and Canada giving workshops and leading retreats designed to help others lead happier lives. He is currently teaching a four- week mindfulness course in Carbondale. He also leads a weekly Mindfulness Group, and a weekly meditation and dharma talk. “The quicker we identify our emotions, the more skillfully we can respond to them instead of simply reacting to them,”

Bruna said. Bruna said he believes that one of the best ways to become aware of one’s emotions and respond appropriately is through cultivating mindfulness throughout one’s daily life, which is an integral part of his teachings. Mindfulness, even practiced for a few weeks, can transform lives, according to Bruna. The key to mindfulness is training the mind, which is done through meditation. “Meditation settles the mind, bringing it back to its natural state,” he said.

At the end of 2011, Bruna said he transitioned from the life as a Tibetan Buddhist monk to a layperson because he felt he could be more effective, reaching more people as a layperson than as a monk. In 2012, he founded the non-profit Way of Compassion Foundation, with the mission of helping people live meaningful lives according to their own values and spiritual beliefs. The foundation operates on donations he receives from his workshops and public talks and from sponsors. Desiring to offer mindfulness training that was practical, accessible and universal, Bruna, along with Australian colleague Mark Molony, created a curriculum for a comprehensive mindfulness course that is adaptable to all types of specific audiences from the general public, to educators, therapists and recovery programs among others. The goal is to help participants live a meaningful life according to their own values, while cultivating emotional and “attentional” balance.

For more information about the weekly groups of both organizations see mindfullifeprogram.org and wayofcompassion.org, or call 970-633-0163.

Three Ways Mindfulness Reduces Depression

By Emily Nauman | June 2, 2014 | Greater Good

Research says that Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy is an effective treatment for depression. A new study finds out why.

Sixty percent of people who experience a single episode of depression are likely to experience a second. Ninety percent of people who go through three episodes of depression are likely to have a fourth. But help is available: The 8-week Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) program been shown to reduce the risk of relapse.

How does it work? To find out, researchers in the United Kingdom interviewed 11 adults who had experienced three or more episodes of severe depression, and had undergone MBCT within the previous three years.

They analyzed the interviews to create a model, published in the journal Mindfulness, to demonstrate how MBCT enables people to relate mindfully to the self and with others. The key, it seems, lies in the way MBCT enhances relationships: Less stress about relationships in turn helps prevent future episodes of depression. Three specific themes emerged from the study:

1. Being present to the self: Learning to pause, identify, and respond

Mindfulness practices of MBCT allowed people to be more intentionally aware of the present moment, which gave them space to pause before reacting automatically to others. Instead of becoming distressed about rejection or criticism, they stepped back to understand their own automatic reactions—and to become more attuned to others’ needs and emotions. Awareness gave them more choice in how to respond, instead of becoming swept up in escalating negative emotion.

2. Facing fears: It’s ok to say “no”

Participants also reported that they became more assertive in saying ‘no’ to others in order to lessen their load of responsibility, allowing them to become more balanced in acknowledging their own as well as others’ needs. The authors speculate that bringing mindful awareness to uncomfortable experiences helped people to approach situations that they would previously avoid, which fostered self-confidence and assertiveness.

3. Being present with others

Being present to others enabled people to bring more attention to relationships and to appreciate their time with others. They talked about how being present to others helped them let go of distressing histories, allowing them to relate to others in new ways. Disagreements also became more constructive, as participants were able to identify their communication problems, and were better able to take on another’s perspective and focus on potential solutions.

Study participants also described having more energy, feeling less overwhelmed by negative emotion, and being in a better position to cope with and support others. Getting through difficulties with significant others through mindful communication helped them feel closer, and having the energy and emotional stamina to spend more time with family members helped them grow together.

Many participants said that as time went on, the benefits of MBCT permeated their whole life. “Through relating mindfully to their own experiences and to others, they were feeling more confident and were engaging with an increased range of social activity and involvement,” write the authors.

The researchers write that in the future, interventions could be place a more explicit focus on approaching relationships with mindfulness. This focus could reinforce the benefit of MBCT, and perhaps lead to even better outcomes in reducing the risk of relapse for people with chronic depression.

AN ANTIDOTE FOR MINDLESSNESS

In the mid-nineteen-seventies, the cognitive psychologist Ellen Langer noticed that elderly people who envisioned themselves as younger versions of themselves often began to feel, and even think, like they had actually become younger. Men with trouble walking quickly were playing touch football. Memories were improving and blood pressure was dropping. The mind, Langer realized, could have a strong effect on the body. That realization led her to study the Buddhist principle of mindfulness, or awareness, which she characterizes as “a heightened state of involvement and wakefulness.”But mindfulness is different from the hyperalert way you might feel after a great night’s sleep or a strong cup of coffee. Rather, Langer writes, it is “a state of conscious awareness in which the individual is implicitly aware of the context and content of information.” To illustrate the concept—or, rather, its opposite—Langer often recounts a shopping experience. Once, when Langer was paying for an item at a store, a clerk noticed that the back of her credit card wasn’t signed. After asking her to sign it, the clerk compared the scrawl on the receipt with the one on the card, to insure that no fraud was being committed. That, says Langer, is perfect mindlessness.

One of the first cognitive scientists to study mindfulness in an experimental setting, divorced from its spiritual trappings, Langer remained for years a lonely voice. But the past decade or so has seen a tremendous uptick in empirical research, as scientific collaborations with nontraditional schools, like the Dalai Lama’s Mind and Life Institute, have become more mainstream. We now know, for instance, that even brief mindfulness practice—typically, a kind of meditation that focusses on a particular aspect of the present moment, like your breath, your body, or a particular sensation—has a substantial positive effect on mental well-being and memory. It also appears to physically improve the brain, strengthening certain neural structures that are tied to heightened attention and focus, and bolstering connectivity in the brain’s default mode network, which is linked to self-monitoring and control.

When Amishi Jha, a neuroscientist who directs the University of Miami’s Contemplative Neuroscience, Mindfulness Research, and Practice Initiative, first began researching the effects of mindfulness on cognitive performance, in the early aughts, most of the existing studies focussed on what could be easily tested: the effects of short bouts of intense practice onimmediate cognitive performance. There had been comparatively little work done on the lasting impacts of mindfulness training, especially under conditions of high stress—the equivalent of evaluating the impact of a week of training on the results of a two-hundred-yard dash versus examining the effects of months of training on a marathon time. “The bulk of my work looks at high-stress cohorts, to see how mindfulness training can be protective against long-term stress,” Jha told me. It was also unclear how little meditation one could get away with and still emerge more mindful. “How low can you go? How little time can it take to sufficiently train people?” Jha said.

To test both the long-term impact of mindfulness and whether there might be a meditation equivalent of “Seven-Minute Abs,” Jha took a set of University of Miami students and split them into two groups, one that would receive mindfulness training and another that wouldn’t. “Their stress goes up throughout the semester, so you can really track performance over time—the natural decline caused by stress,” she said. The semester-long test would allow her to see whether mindfulness could benefit people in an increasingly hostile mental environment.

Jha designed a series of short, weekly training sessions, where students learned the basics of mindfulness theory and how to practice it—for instance, learning to focus on their breath while dismissing any intruding thoughts. In addition to a twenty-minute session with an instructor, they were asked to come in for two twenty-minute practice sessions each week, for seven weeks. The combined hour of instruction and practice each week was far less extreme than previous mindfulness-training courses that Jha had developed; one that she created for the military totalled twenty-four hours of practice.

About two weeks into the semester, before the training began, the students were asked to complete several tests. First, they performed a series of tasks that required sustained attention. In one, they watched a string of digits appear on a screen, and were told to press the keyboard’s space bar every time a new digit appeared, unless that digit was a “3.” At a few points in the study, the flow of digits was interrupted by questions about the participant’s attention span. In two subsequent tests, the students were assessed on their working memory capacity (how many letters in a list could they remember after solving an unrelated math problem?) and delayed-recognition working memory (could they quickly and accurately distinguish a face they had already seen from a set of new faces?). All of the students performed at roughly the same level.

Nine weeks later, when the students were tested again, large performance gaps had emerged: as the semester dragged on, the control group performed worse than they had originally, while the students who received mindfulness training became more accurate and focussed. Jha’s regimen, it seemed, wasn’t just a way to get better; it was a way to keep from getting worse.

Mindfulness training, Jha hypothesizes, may work as a protective factor against the typical stresses of student life—or any stress, for that matter, since it improves emotional equilibrium and enables people to better handle distractions. “It’s similar to how physical exercise can change the body,” Jha said. “We know that physical activity helps our bodies, but we’re just coming to the understanding that mental exercise is also critical to promoting mental well-being. It’s a cultural shift.”

Shauna Shapiro: How Mindfulness Cultivates Compassion

Author and researcher, Shauna Shapiro, explores how moment-to-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, and surrounding helps us to see and alleviate suffering in others.

From the Science of a Meaningful Life Video Series

Meditation transforms roughest San Francisco schools

At first glance, Quiet Time – a stress reduction strategy used in several San Francisco middle and high schools, as well as in scattered schools around the Bay Area – looks like something out of the om-chanting 1960s. Twice daily, a gong sounds in the classroom and rowdy adolescents, who normally can’t sit still for 10 seconds, shut their eyes and try to clear their minds. I’ve spent lots of time in urban schools and have never seen anything like it.

This practice – meditation rebranded – deserves serious attention from parents and policymakers. An impressive array of studies shows that integrating meditation into a school’s daily routine can markedly improve the lives of students. If San Francisco schools Superintendent Richard Carranza has his way, Quiet Time could well spread citywide.

What’s happening at Visitacion Valley Middle School, which in 2007 became the first public school nationwide to adopt the program, shows why the superintendent is so enthusiastic. In this neighborhood, gunfire is as common as birdsong – nine shootings have been recorded in the past month – and most students know someone who’s been shot or did the shooting. Murders are so frequent that the school employs a full-time grief counselor.

In years past, these students were largely out of control, frequently fighting in the corridors, scrawling graffiti on the walls and cursing their teachers. Absenteeism rates were among the city’s highest and so were suspensions. Worn-down teachers routinely called in sick.

Unsurprisingly, academics suffered. The school tried everything, from counseling and peer support to after-school tutoring and sports, but to disappointingly little effect.

Now these students are doing light-years better. In the first year of Quiet Time, the number of suspensions fell by 45 percent. Within four years, the suspension rate was among the lowest in the city. Daily attendance rates climbed to 98 percent, well above the citywide average. Grade point averages improved markedly. About 20 percent of graduates are admitted to Lowell High School – before Quiet Time, getting any students into this elite high school was a rarity. Remarkably, in the annual California Healthy Kids Survey, these middle school youngsters recorded the highest happiness levels in San Francisco.

Reports are similarly positive in the three other schools that have adopted Quiet Time. At Burton High School, for instance, students in the program report significantly less stress and depression, and greater self-esteem, than nonparticipants. With stress levels down, achievement has markedly improved, particularly among students who have been doing worst academically. Grades rose dramatically, compared with those who weren’t in the program.

On the California Achievement Test, twice as many students in Quiet Time schools have become proficient in English, compared with students in similar schools where the program doesn’t exist, and the gap is even bigger in math. Teachers report they’re less emotionally exhausted and more resilient.

“The research is showing big effects on students’ performance,” says Superintendent Carranza. “Our new accountability standards, which we’re developing in tandem with the other big California districts, emphasize the importance of social-emotional factors in improving kids’ lives, not just academics. That’s where Quiet Time can have a major impact, and I’d like to see it expand well beyond a handful of schools.”

While Quiet Time is no panacea, it’s a game-changer for many students who otherwise might have become dropouts. That’s reason enough to make meditation a school staple, and not just in San Francisco.

David L. Kirp, a professor of public policy at UC Berkeley, is the author of “Improbable Scholars: The Rebirth of a Great American School District and a Strategy for America’s Schools.”

David L. Kirp

SFGate – Published 6:37 pm, Sunday, January 12, 2014